Are you thinking about designing a backend API? You probably already know about REST architecture. You might even know that the REST architecture doesn’t handle complex applications very well.

If so, you might be struggling to answer the following questions:

-

How much data should I return with each endpoint?

-

Will I return the same data on mobile as to desktop devices?

-

Do I want to have real-time updates if something changes?

Enter GraphQL. In this post, learn everything you need to know about GraphQL. Discover GraphQL’s benefits and limitations and decide whether it’s the right tool for your backend API project. 🙌

The Problem With REST

REST stands for REpresentational State Transfer, where endpoints are structured around objects, like users, groups, comments, etc.

REST is a specification that has been around for a long time, and today it’s still the most standard, widely-accepted way to write an API. Despite REST maturity, the main issue spins around one question.

What data should I return by my endpoints?

One business case you might encounter is a need to display a list of users and a list of each user’s recently added comments.

In other words, fetch a list of entities, and for each entity, fetch another related list of entities. There are two ways of solving this problem using REST.

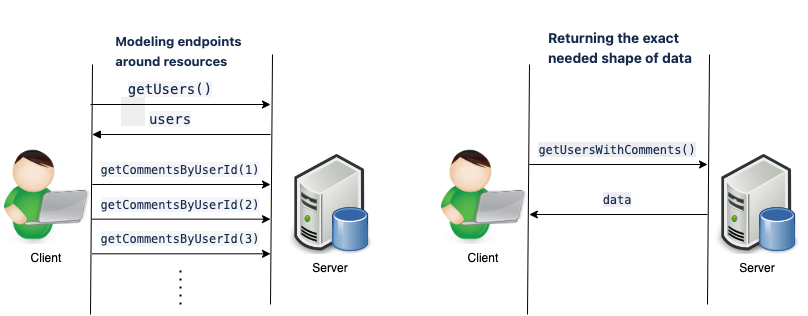

Modeling Endpoints Around Resources

Having one endpoint per resource is a very maintainable approach for backend developers. It is relatively scalable but introduces unnecessary complexity on the client side, meaning the client needs to make multiple API calls to structure a data model. In this example, you could have the following endpoints:

-

getUsers()- return a list of users -

getCommentsByUserId(userId: string)- returns a list of comments for a specificuserId

Using a resource-based approach, a relatively common N + 1 problem can arise, where the client side is required to call the server N + 1 times to fetch one collection of resource + N child resources.

const getUserWithComments = async (): Promise<User[]> => {

// fetch a list of users

let users = await getUsers();

// new HTTP request for each user

for(let i = 0; i < users.length; i++){

const user = users[i];

// loading comments from the server

user.comments = await getCommentsByUserId(user.id);

}

return users;

}Resource-based endpoints may lead to slow rendering because it takes time to load all the data, and you can overload the server with too many API calls.

Returning the Exact Needed Shape of the Data

Endpoints can also be structured to return the exact shape of data the client wants to work with. You could have an endpoint, such as getUsersWithComments(), that would return users with their comments in one HTTP round trip. This approach works until it doesn’t.

This approach establishes a close relationship between the client and the server. Whenever the management requests to change the UI, where additional data should be displayed or removed, the frontend developers have to contact backend developers to adjust the returning data from a specific endpoint.

This approach is challenging to maintain, especially when considering having multiple endpoints that return some mixed data type for the consumer or having separate endpoints for mobile devices. In the worst case, you could end up with too many endpoints returning a combination of objects, not knowing which endpoints are even used.

What Are My Options?

Delegating the responsibility of defining the returning data shape to the server side, sooner or later, the frontend developers will encounter one of the two problems mentioned above. To put gas into the fire, the following problems in the REST architecture weren’t even mentioned :

-

Sending fewer data to mobile users

-

Having real-time communication

-

Having API documentation (and following it)

The groundwork has been laid. Let’s talk about GraphQL!

What is GraphQL?

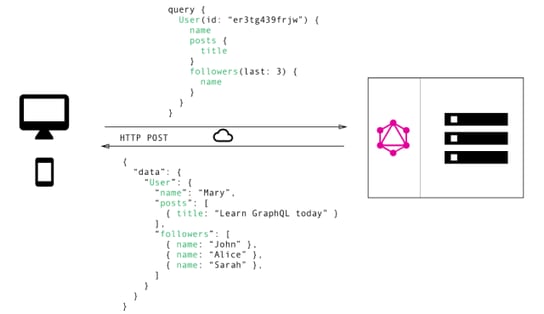

GraphQL is a query language that delegates the responsibility of defining the shape of data being returned from the server to the client by the client. The server provides a playground and documentation for its API, where the client can see all available executable methods. Queries to get data, mutations to modify data, and subscriptions for real-time communication (we will get back to it later).

When calling a server-side method, a JSON data structure is included in the message payload that describes the returning object property fields for which the server has to return value.

Because GraphQL solves under-fetching and over-fetching, the client only gets back data for fields that are included in the payload of the HTTP request. No more, no less.

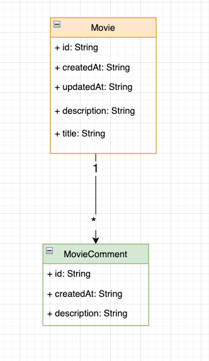

GraphQL Models Relationships ❤️

GraphQL models a relationship between objects. It enables retrieving all required data by one HTTP round trip. Relationship modeling means if an entity has a 1-to-N relationship with another one, we can request this relational information in one query.

GraphQL Resolvers

To resolve object relationships, you guessed it, resolvers are used. A resolver is a function, the main building block why we even consider using GrapQL in the first place, that's responsible for populating the data for a single field for the object type.

Resolvers can be understood as an enhancement to add additional fields for an entity class that doesn’t exist in the database but is calculated on the server side.

Their usefulness lies in their execution. A function registered as a Resolver is not executed until it is called. The code snippet below represents a piece of the above-displayed database UML diagram using the NestJS framework.

@ObjectType()

export class Movie {

@Field(() => Int)

id: number;

@Field(() => String)

createdAt: Date;

@Field(() => String)

updatedAt: Date;

@Field(() => String, {

nullable: false,

description: "User's title to the movie",

defaultValue: '',

})

title: string;

@Field(() => String, {

nullable: true,

description: "User's description to the movie",

})

description: string;

}

@Resolver(() => Movie)

export class MovieResolver {

constructor(private movieCommentService: MovieCommentService) {}

@ResolveField('movieComment', () => [MovieComment])

async getMovieComment(@Parent() movie: Movie) {

const { id } = movie;

return this.movieCommentService.getAllMovieCommetsByMovieId(id);

}

}Loading comments for a Movie object require making an expensive database select operation. Furthermore, you don't always need to load comments for a Movie, only when the user requires them.

Decorating a method with the @ResolveField decorator (NestJS syntax) executes the inside logic only when the client requests data for that field name, in this case, for movieComment.

The API creator should provide descriptions for resolver fields, especially the ones that execute an expensive server-side operation, like database calls, so that the consumers won’t query unnecessary fields just because they can.

Benefits of GraphQL

In the REST architecture, the question that is always present is, “What data does this endpoint return?”. Testing endpoints by Postman, or in better cases, having swagger for backend documentation, still doesn’t guarantee that the returned Object’s properties will not be undefined and are the type that the documentation describes. For a better developer experience, GraphQL provides the following advantages:

-

GraphQL playground

-

Predefined schema

-

Generating TypeScript types

-

Real-time communication

-

Device adaptations

-

Batch query execution

The biggest major benefit worth highlighting is GraphQL decouples the dependency between the server and the consumer.

The consumer only receives back values for fields included in the GraphQL operation. The server can create a very complex schema and offer a return type that has 60+ properties to query, but the consumer will only receive back values for the fields which were included in the GraphQL operation.

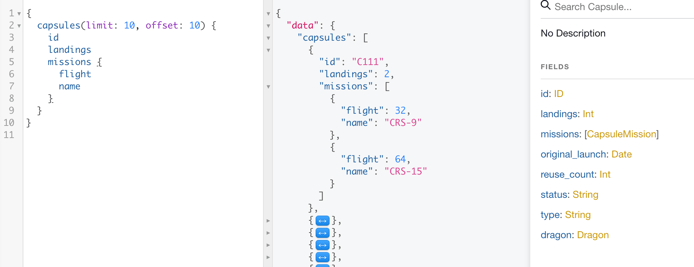

GraphQL Playground

GraphQL Playground is an IDE created and maintained by Prisma. It’s built on top of GraphQL and serves as API documentation for every available query, mutation, and subscription. The consumer can inspect the return type of each operation and test server-side functionalities. For an open API, check out SpaceX GraphQL API.

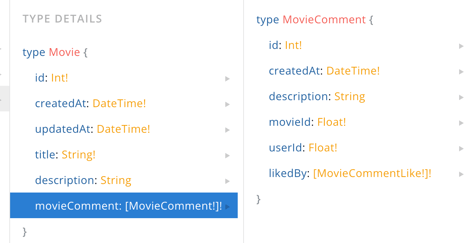

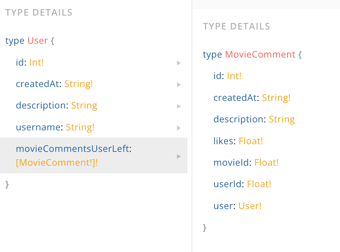

Predefined Schema

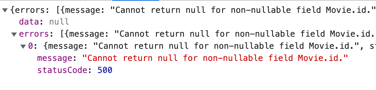

When inspecting GraphQL data types throughout the playground, you might notice some fields include an exclamation mark. (!)

It serves as insurance that the server has to provide the correct data type and can not return a null value for them.

Taking a look at the attached image by querying fields like User.id, User.createdAt, the server will never return a null value for these fields. If it had happened, we would receive the following error from the query operation.

{

"errors": [

{

"message": "Cannot return null for non-nullable field User.id.",

"statusCode": 500

}

],

"data": null

}Using array types, like for the movieCommentsUserLeft: [MovieComment!]!, the outer exclamation mark, []! means that the API will always return back a list of values, even an empty list, and the returned value will never be null.

On the other hand, the inner exclamation mark [MovieComment!] describes that the elements inside the list will always be objects. It is impossible for a null value to be part of the list. If it had happened, the whole query would fail, and no data would have been returned.

Generating TypeScript Types

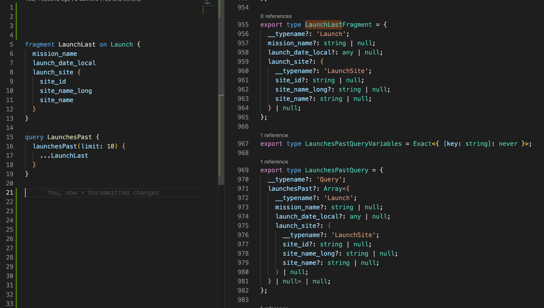

The major benefit of the exposed GraphQL schema is that developers define GraphQL operations and use libraries, such as graphql-code-generator, that allow generating TypeScript types from the server-side schema.

Using a generator prevents manual handwriting of TypeScript Interfaces for all API responses, and if the server-side schema change, the whole TypeScript schema can be regenerated by one command.

An example can be seen in the image below, where at the left, we define a query operation launchesPast expecting a LaunchLast fragment to be returned, and on the right, we see the generated TypeScript types by graphql-code-generator.

Using GrapQL fragments, we can share pieces of logic in multiple queries and mutations that will return the same data type. Generated fragments can then be used for type-checking on the client side.

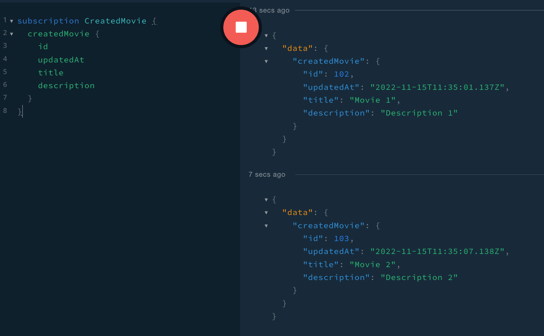

Real-Time Communication

In the traditional REST world, to achieve real-time communication, you need to use WebSockets. You know they suck. What endpoint should I listen to? What data will I receive back? Is the connection alive?

Instead of Polling data from the server, subscriptions are used to listen to asynchronous emitted events. Subscriptions maintain an active connection to the server, listening and waiting for the server to push updates. The main benefit of using subscriptions is the type safety, such that, as in queries, the consumer can select which fields to receive values back.

Device Adaptations

This is more or less just a piece of advice. When working on a small screen device, like a mobile phone, you usually don’t show as much data compared to a desktop resolution. Therefore it is not required to fetch as much data as a desktop device.

The solution you may go with is to create two separate queries for the same operation, one for a desktop device to fetch a large quantity of data and one for a mobile device to load less data and use conditional statements to execute them based on the client’s device.

Batch Query Execution

Having a GraphQL API, you can execute multiple queries at once by sending one HTTP request. Taking a look at SpaceX API, you can select multiple independent queries and fetch data in one round trip.

{

launchesPast(limit: 3) {

mission_name

launch_date_local

launch_site {

site_name

}

}

historiesResult(limit: 3) {

data {

details

}

}

missions(limit: 3) {

name

twitter

}

}Drawbacks of GraphQL

There has never been a point in time when technology was so great that it would not have any downside. Let’s take a look at some concerns you have to be aware of when choosing GraphQL architecture.

N + 1 Problem

Once you start learning about GraphQL, the first problem you hear about is the “N+1 problem”. Let’s describe an example scenario by the SpaceX API of how it may happen.

You want to fetch past launches from one table, and for each of them, you want to get the site_name from another table. Using REST, you may have the following endpoint.

route: '/launches/past',

method: 'GET',

queryParam: 'limit'that could result in the following Database calls

SELECT * FROM launches limit = {limit};

-- pass the fetched launches.ids the the second query

SELECT * FROM launch_sites WHERE launch_id in (1, 2, 3);With two queries, you will have your desired result. Beware that this works because you have already loaded a list of launches, and you pass their launch.id to the second query.

In GraphQL, to load launch_sites from a different table, you would probably use resolvers attached to the Launch entity, like in the following snippet.

schema = `{

type Query {

launchesPast(limit: Int!): [Launch!]!

}

# from table launches

type Launch {

id: Int!

mission_name: String

launch_site: [Launch_sites!]!

}

# from table launch_sites

type Launch_sites {

id: Int!

site_name: String

}

}`

resolvers = {

Query: {

launchesPast: async (_: null, args: { limit: number }) => {

return ORM.getAllLaunches(limit)

}

}

Launch: {

launch_site: async (launchObj, args) => {

return ORM.getLaunchSitesById(launchObj.id)

}

},

}However, suppose you execute the below query. In that case, you will create N database calls for N Launches to get their site_name because every resolver function only knows about its parent, and GraphQL executes a separate resolver function for every field.

query LaunchesPastQuery($limit: Int!) {

launchesPast(limit: $limit) { # fetches Launch entities (1 query)

id

mission_name

launch_site { # fetches Sites for each Launch (N queries for N Launches)

site_name

}

}

} # Therefore = N + 1 round tripswill translate to the following pseudo-SQL:

SELECT * FROM launches limit = {limit};

-- pass the fetched launches.ids the the second query

SELECT * FROM launch_sites WHERE launch_id in (1);

SELECT * FROM launch_sites WHERE launch_id in (2);

SELECT * FROM launch_sites WHERE launch_id in (3);The N+1 problem is further exacerbated in GraphQL because neither clients nor servers can predict how expensive a request is until it’s executed. In REST, costs are predictable because there’s one trip per endpoint requested. In GraphQL, there’s only one endpoint, and it’s not indicative of the potential size of incoming requests.

Facebook previously introduced a solution to the N+1 issue by creating DataLoader, a library that batches requests specifically for JavaScript. Also, Shopify took DataLoader as inspiration and built the GraphQL Batch Ruby library.

What DataLoader does is wait for all resolvers to load in their individual keys and then hit the database once with the keys, and return a promise that resolves an array of the values. It batches queries instead of executing them one at a time.

N+1 is the biggest problem you may encounter by having a GraphQL server. Before implementing the server-side logic, you need to have a rough understanding of how entity relationships will be resolved because once you deal with a large database and millions of data, having a bad implementation will hugely increase your tech debt and massively impact the performance of the application.

Schema Dependency

Having a predefined schema that is being exchanged between the server and the consumer is advantageous, even so, when the exclamation mark (!) is used on type fields so that the consumer knows which fields will never have a null value.

Exclamation marks or so-called not-null values can, however, ruin the whole query. Let’s have an example that, for some Launch entity, it saved ID column in the database, or any column that must have a present value, will suddenly be null (code snippet on line 17.).

schema = `{

type Query {

launchesPast: [Launch!]!

}

# from table launches

type Launch {

id: Int!

mission_name: String

}

}`

resolvers = {

Query: {

launchesPast: async () => {

const allLaunches = await ORM.getAllLaunches()

allLaunches[3].id = null; // <-- will cause the query to fail

return allLaunches;

}

}

}If the consumer requests a list of Launch entities by the launchesPast query, the whole query will fail and you will receive the following error message:

Cannot return null for non-nullable field Launch.idIn conclusion, if you query a list of objects, and only one of them does not match the returning schema (it has a null value for a field that has the exclamation mark (!)), then your whole query will fail, and you will not receive back any data.

Nested Recursion

As a query language for APIs, GraphQL gives clients the power to execute queries to get exactly what they need. But what if a client sends a query asking for many fields and resources? With GraphQL, users can’t simply run any query they want.

authors {

name

books {

title

authors {

name

books {

title

authors {

name

}

}

}

}

}I think you can see the problem here. A GraphQL API must be carefully designed, and to prevent such a nested data loading, you can use libraries like graphql-cost-analysis to set a maximumCost for your whole schema and, for each operation, define a complexity value. So when the consumer uses your API, the sum of all complexity from each operation can not exceed the total maximumCost. Otherwise, the consumer’s request will be blocked.

HTTP Status Codes

Whenever Apollo Server encounters errors while processing a GraphQL operation, its response to the client includes an errors array containing each error that occurred. Despite any occurred error, the status code of each request will have a code 200, but the returned payload will have a list of occurred errors with the statusCode of 500.

Error code 500 is not necessarily the best way to notify your consumers that something went wrong. You want to use status codes for unauthenticated/unauthorized requests, redirects, etc. For information on configuring error handling on the server side, check out Apollo server Error handling.

Scaling with Subscriptions

As previously mentioned in the Real-time Communication section, subscriptions are a helpful feature in GraphQL for asynchronous emitted events from the server side. The problem is with scaling the server horizontally into multiple instances to manage request overload.

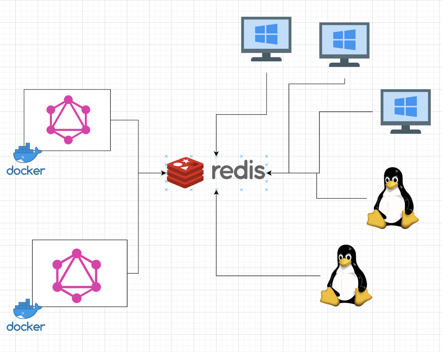

If you use subscriptions to notify a group of users and you have multiple instances of your backend application, you never want your clients to be directly connected to a specific instance. What may happen is that one GraphQL instance pushes data via subscription, but clients who are connected to a different instance will not be notified about that change. Consider using Redis as your load-balancer. Read more about GraphQL subscriptions with Redis Pub Sub.

Do I need a GraphQL server?

The battle between GraphQL vs REST has been ongoing for quite some time. Primarily because these two API styles have different approaches when dealing with data transfer over internet protocols.

For most applications, there won’t be any increase in performance by simply migrating to GraphQL. However, when an app starts to scale, that is when the value of migrating to GraphQL comes to play. It presents a powerful and elegant solution for teams that have been restricted to the traditional REST API. Also, a common case for a GraphQL can be to hide multiple complex systems behind it, legacy infrastructures, or third-party APIs that are enormous in size and difficult to maintain and handle.

When considering the adaption of GraphQL, it may be useful to read the journeys of other companies implementing it. You may be interested in PayPal's Adoption of GraphQL, Netflix's Rapid Development with GraphQL Microservices, or Shopify's New Admin API in GraphQL.

Summary

Choosing the right tech stack or architecture design for an application is never an easy decision. You have to consider the problems each decision solves and the complexity it brings.

Through this article, you learned what GraphQL is, why developers, especially frontend developers, love it so much, how it can improve your development journey, and also what concerns to be aware of.

For more information, check out our training program, Bitovi Academy, BitoviClient Work, or book a free Consulting call to talk to an expert one-on-one!

Do you have thoughts about this post?

We’d love to hear them! Join the Bitovi Community Discord to talk tech with us. 🥚

Previous Post